Why it Matters, and What to Do about It.

On my own journey as a man (as well as a psychotherapist, father, and partner), I am met, increasingly, with parts of myself that don’t feel good or initially make sense. They often perplex me with their seeming immaturity and impetuousness.

So much so, that my first reaction is to suppress what wants to come out of me for fear that I will be seen as childish. As it turns out, those parts of me are very young, have been pushed down for years, and are asking — and sometimes shouting — for my attention.

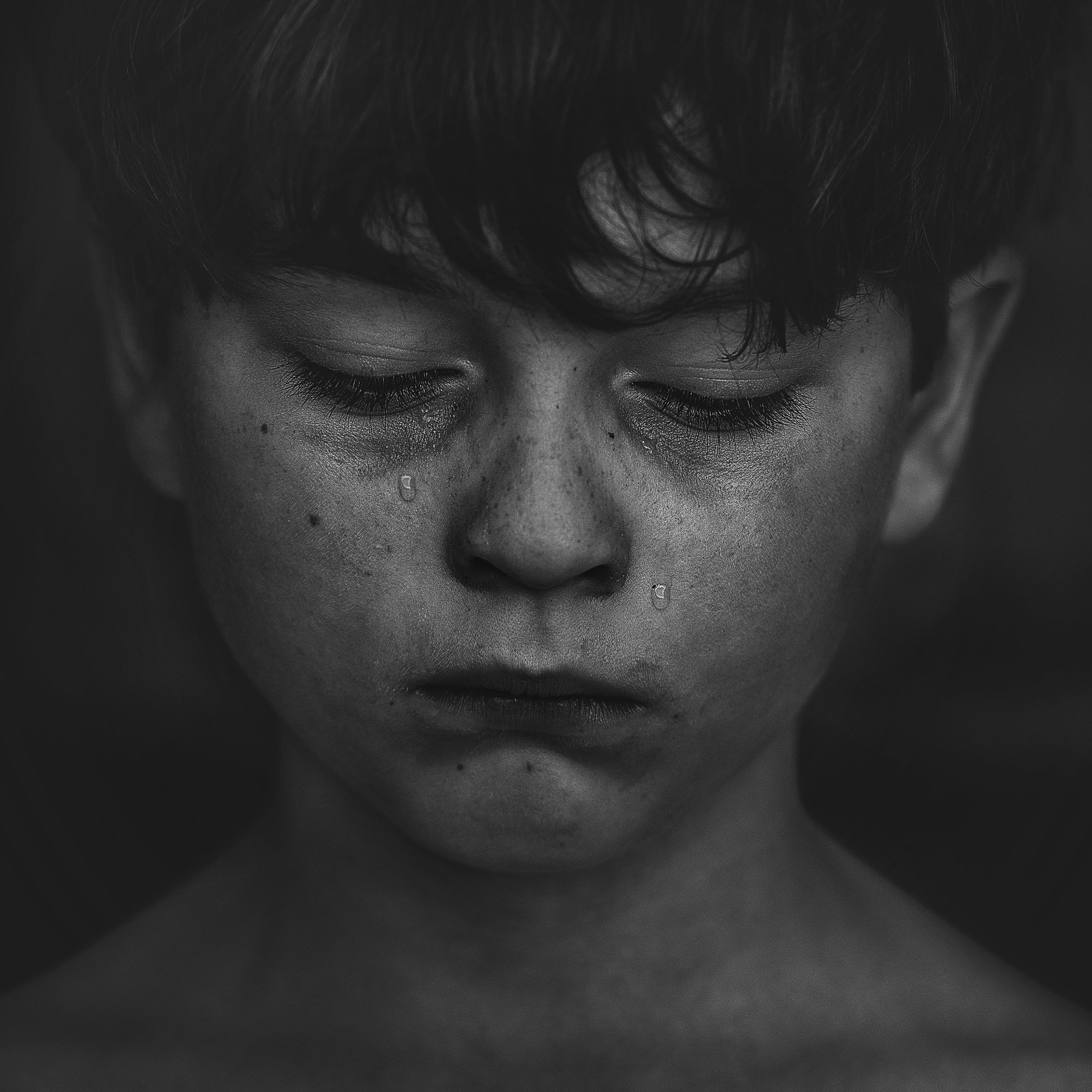

This is my wounded boy.

What do I mean when I say, “wounded boy,” and why would you want to find him?

Simply put, our wounded boy is the untended, unacknowledged, and often calcified wounds that we men feel—wounds that originate from all we did wrong, all we couldn’t get right in the eyes of those that mattered most, and the ways we were harmed in our youth.

Why work to find him? Well, because he holds the key to unlocking much of your life force, generativity, creativity, Eros, and aliveness that you long to feel again.

To get at what I mean here — as well as more of the “why” — I’ll use an example from my own partnership to illustrate what I’m speaking to.

My partner is a powerful woman who I find to be equal parts brilliant, fierce, tender, and loving. With that, she’s also sometimes relentless in her intensity around commitment to purpose, awareness, and growth — hers, her community’s, and sometimes , especially, mine. At times, this intensity comes from her own wound story of being all alone in her life with no one to help her make the world a better place.

Her vigilance around what I am doing and who I am often makes me feel as if she’s “picking” or “poking” and can trigger a fear response in my nervous system.

This place of fight/flight/freeze is where my wounded boy shows up most reliably.

My feelings about those kinds of experiences from my past shows up in the present and trigger the boy in me who is terrified that he will be physically harmed (I was), or, in a more mythological sense, destroyed. He’s failed to meet the mostly unspoken expectations made of him.

In this triggered place, even the smallest question around what my intentions are can activate the boy who feels powerful shame for not being right, for not being enough, and for committing the deeply dangerous act of getting it wrong.

So, how do we begin to love our wounded boy?

1. Get to know him.

Once you’ve identified him, you can begin to learn where he shows up in your life, how he shows up, and how he gets in the way of you having healthy, generative, adult relationships. To use me as an example, when I am intensely defensive, that’s my wounded boy showing up. For me, this can look like stoicism, making the other person wrong without telling them, having a “f*ck off” attitude, and occasionally acting out.

With just a little awareness and skill in this new and conscious way of being, this defensiveness can now act as a signal that we’re sensitive and triggered. Paying attention to this allows us to stay more present, speak to our whole experience—”Honey, I hear you and I want to stay present, but I am noticing that I am getting activated and need to take a minute to down-regulate. I’ll be back soon”—and stay in connection with ourselves and our partners.

2. Learn to love him.

This one’s hard at first. Loving a part of ourselves we have spent most of our lives denying, avoiding, belittling, shaming, and repackaging can be tough. I’m still squeamish about this process because, when I identify that I am in my wound and there is someone there to see it, it can feel like sh*t.

I’m training myself — through sense awareness, self-love, a solid breathing practice in my hardest places, and deep, consistent conversations with all of my people— to curb my long-held habits of shutting down, getting pissed and defensive, or ignoring my wounded boy altogether.

Instead — and this practice is vital — I am interrupting those behaviors and substituting new ones. I am slowing down, breathing, taking time to myself when needed, and letting my partner and others see this part of me.

It’s liberating (and terrifying), and it gets easier— not easy, but easier.

3. Introduce him to those closest to you.

This might be the hardest part of the whole process. When our (self-described) ugliest, least evolved, most shameful parts come out, it is usually either when we are stressed or otherwise poorly resourced (think arguments, road rage, sleep deprivation, marital spats).

The different path I am suggesting here is to build agency by proactively sharing these parts of yourself before you are in conflict. In the process, you end up reshaping your body’s reaction to these aspects of you through your vulnerable, courageous admission of their presence, while incrementally transmuting that habitual reaction into a healthier, agentic, learned response.

The other powerful bonus is that, in the process, you become more and more known to those you love the most. They begin to see more of who you are. By doing this, the folks in your community that you share these parts of yourself with now can become your advocates, helping you to see yourself more clearly and work with these hard-to-see places more effectively.

So, my advice to those of you wanting to know, love, and heal your wounded boy, is to share these parts with those who feel safe to you. It might only be your journal at first, or your dog. Maybe it’s your best friend. Perhaps it’s your partner.

Two more vital points: This won’t happen all at once—in fact, it can’t. So expect to feel familiar feelings while also working to act differently when they arise. This process will be messy—sometimes, very messy. And that is okay, and is truly, absolutely necessary. If we try too hard to get it right and work to have everything be smooth and beautiful, then we miss the point and we miss ourselves in the process.

And, lastly, be kind to yourself; be gentle with your little guy because he deserves your love.

He is you, after all.

Author: Jeff Howard

Editor: Callie Rushton

Published in Elephant Journal